Two contrasting but equally clichéd narratives are coming in the way of our devising a robust and competitive wool policy that leverages our domestic resources better.

One is the outraged assertion that we have the world’s second largest sheep population, produce 40 million kilos of wool every year, but discard 32 million kilos out of it and import 80 million kilos, paying INR 2,000 crores. The counter is that Indian wool is largely short-staple, coarse wool, unsuitable for apparel; that our INR 10,000 crore handmade carpet industry, the world’s largest exporter, has moved away from the hand-knotted carpets for which much of our wool is suitable; synthetics are further reducing wool demand, and the procurement, transport and processing of Indian wool is too problematic given the mobility and supposed backwardness of sheep herding communities.

We need to go beyond this binary. One major problem has nothing to do with our wool quality; it is the inexplicably low 15% import duty that lays out a red carpet for foreign sourcing, including the unchecked entry of wool waste masquerading as wool. This invitation to dump must be withdrawn. Wool imports certainly have an important place in areas such as apparel, which provide employment and boost GDP and foreign exchange reserves, since only 5% of our own wool is apparel grade. Also, we have Asia’s largest wool trade hub, and wool from all over the world is bought, processed and sold here, again generating jobs and revenues. But if we rationalize duties and block waste imports, at least one sizeable demand, namely for average quality wool to mix with superior grade for blankets and the like, can be fed by domestic wool. Side by side, we must also revive the hand-knotted carpet industry, since 85% of Indian wool is carpet grade. If we can boost wool GDP in this way, we may not need to import vast quantities of rags, i.e., used clothes, and extract their waste fibres to make low-quality garments for their economic value.

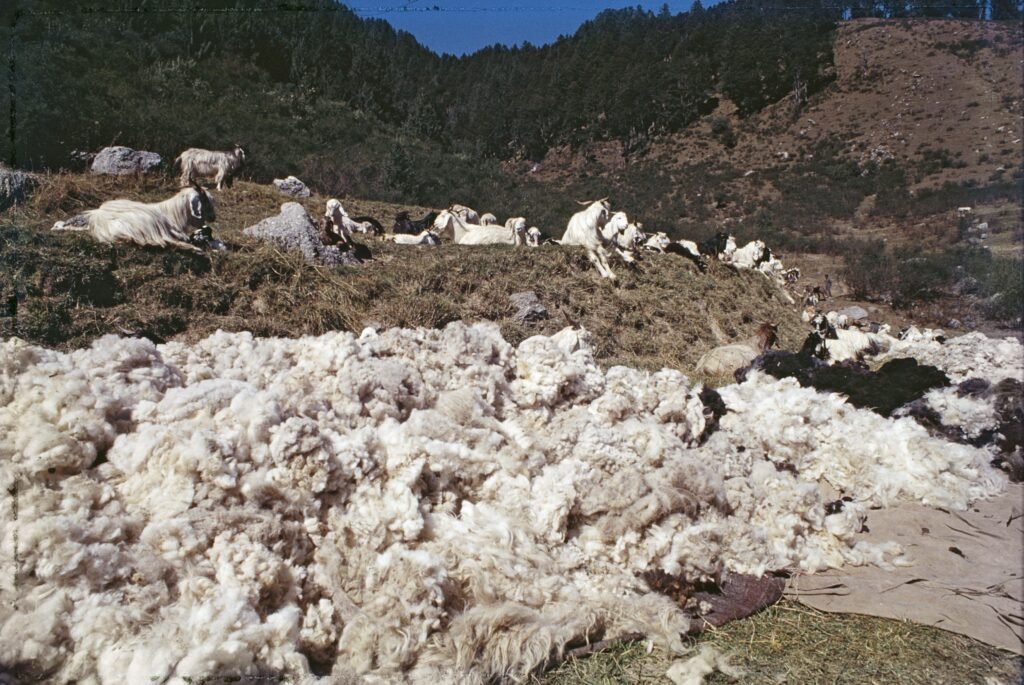

The second issue is the need to work on procurement and primary processing to strengthen the domestic supply chain. Virtually all of India’s sheep are reared by mobile herding communities that have historically engaged largely with traditional, local handicrafts markets. Traders say that when herders bring their wool to markets it is rarely sorted by colour and quality. Training programmes for herders on cleaning and sorting raw wool plus systematic efforts to promote herder-trader interactions can help resolve some of these problems. We also need to invest in R&D for the primary processing of indigenous wool in rural areas.

But the issue is also one of aggregation from mobile herding communities. While this seems a difficult business, one may draw a useful parallel with our dairy industry, where mechanisms have been successfully deployed to collect milk from mobile herders, including camel milk from widely dispersed ones. In fact, the aggregation process there actually provides employment to herder youth. And we must bear in mind that milk requires much more stringent quality testing and a high-tech cold chain.

Economies the world over develop high-value niche markets for heritage resources and handicrafts that, beyond being iconic ambassadors of a country, keep knowledge systems of production and craft alive and foster local economies. We still have such economies and ecosystems in several parts of the country, linking herders with crafts persons and local consumers on a community-to-community basis. Traditional wool products continue to play roles far beyond the utilitarian or fashionable ones we might imagine, being a part of rites of passage, exchanges in relationships and sacraments. They are created through handicrafts techniques that are, unlike modern machinery, ideally suited to working with coarse wools. There are currently some efforts here and there to adapt these traditional textiles to designer products for urban markets while supporting and promoting the producers. There is a need to promote and support such initiatives on a much larger scale, with designer products being inspired by and sustaining traditional ones.

But the biggest opportunities lie in innovative technical uses. Few of us realise that wool isn’t just something that keeps you warm. It’s an all-weather thermal insulant, keeping rooms warm in winter and cool in summer; a home air purifier that neutralises toxic emissions without using electricity; it regulates humidity by absorbing and releasing moisture from the air; it’s an acoustic insulant, reducing ambient sound levels. Wool insulation can be installed and used without protective gear unlike synthetic insulants. It retards fire without releasing toxins, unlike synthetic retardants. It’s created naturally, without factories or fuel, and requires very little for processing. It’s completely recyclable and biodegradable, and has a low environmental footprint. Finally, wool mitigates climate change and it doesn’t harm the ozone layer. Thus, it has potential as a replacement for thermocol, rock wool, glass wool, polyurethane foam and PET in thermal and acoustic insulation in built spaces as well as in packaging for temperature-sensitive perishables.

What better place to think outside the box than in the ocean? Wool is unparalleled in its ability to adsorb oil, and this has a vital application. Oil spills caused by maritime disasters lead to massive and long-lasting ecological damage. Wool has been used with superb efficiency to clean up such spills. Wool wads are also used in a big way in ammunition manufacture in the defence industry where they outperform all other materials. Beyond this, there is the use of wool as a nutrient-rich biofertilizer. An insightful wool policy must recognize the huge opportunities in all these innovative applications, because, by and large, they can make use of any quality of wool. That is where we can really leverage the 32 million kilos we are throwing away every year and reduce the high energy use and harmful effects of synthetics, while putting an abundant resource to good use.

A policy must recognize the people it serves. Our remarkable mobile herding communities or pastoralists that have skillfully bred at least 44 recognised indigenous breeds of sheep perfectly suited to their respective climatic zones and terrains. There may be a role for fine-wool-bearing hybrids of Indian and foreign breeds such as Bharat Merino and Rambouillet-infused stock. But indigenous breeds are far hardier, require less maintenance and have greater predator wariness. Despite this, today a herder earns only around a measly Rs.350 per year from wool sales, and official recognition of pastoralist-origin breeds too is negligible. It’s little wonder that pastoralists are switching in a big way to breeding sheep for meat. Such communities, however, as keepers of genes, always maintain a few wool-value animals in their herds, because of their unique recognition of the need to adapt to unforeseen changes in circumstance. An enlightened wool policy must make use of this ingenious trait and safeguard our native wealth.

In a nutshell: (1) We cannot waste 32 million kilos of wool each year. (2) Import duties must be rationalised. (3) A country with an abundance of short-staple coarse wool must invest in short-staple, coarse wool. (4) It’s absurd not to plough 85% of our wool into the carpet and other industries it’s suited to. (5) We must enhance rural procurement capabilities. (6) Education, technology and entrepreneurship for Indian wool all need to be boosted. (7) Good planning needs good data. (8) R&D for innovative uses of short-staple, coarse wool is of vital importance. (9) Our shepherds, wool crafts communities, sheep breeds and their ecosystems must be recognised and valued.

The government has been considering initiating a National Wool Mission. Nothing can be more timely, especially if it takes all these essential facets of our wool scenario into account, upscales the initiatives and innovations currently being worked on and pushes back against attempts to dictate our policy at the cost of our economy and our people.